When I read the first news about the vehicle that drove into a café in the German town of Münster last Saturday I was shocked. Not because the incident happened – in a way I’m getting used to news like this but because of the place where it happened. I lived in Münster for five years between 2010 and 2015 and the place of the attack was only a maximum five minutes walk from my home and it’s a place I surely have passed over 100 times. I’m grateful that no one of my friends, who are still living there where injured or killed in the attack. In a way I was also relieved when it became clear that the perpetrator was neither a Muslim nor a refugee, because so it is harder to use the attack to spread Islamophobia and fears against refugees and asylum seekers (even if right wing activist where still trying to do so…).

A lot of people outside of Germany might not have heard about Münster before the attack or might not know a lot about it. And if they know something about Münster it might be that it’s Germany “bicycle capital”, that it has a large university, that it has a beautiful (destroyed and reconstructed) old town or that it won a price as one of the most liveable places in the world in 2004. Today I want to tell you the story of Münster as a place which has a long history of anti-radicalism and peace building – especially between faith communities.

Münster exists since the time of Charlemagne and is home of a Roman-Catholic diocese since the year 800. Because of this long lasting history (Catholic) Christianity is still relatively dominant in Münster’s city culture and visible through a lot of (huge) churches all over the area. The first time Münster became really important for (world) history was in the year 1534. As part of the protestant reformation radical “Anabaptists” established a theocracy in Münster. Only a (united!) military force of Catholics and Protestants was able to establish the former order in the town after about one year of resistance. Of course neither the Anabaptist with their theocracy nor the military action by Protestants and Catholics a good example how to deal with differing religious views – but this experience and the remembrance of it might have helped the citizens to be very sceptical against any kind of extremism.

The next time Münster became important in world history – and this is probably the moment when Münster was most prominent in its long lasting history – was in 1648. After 30 years of war in Germany, in which all major European powers have been involved and more than 100 years of conflict as a result of the protestant reformation Münster and it’s neighbouring town in the north Osnabrück were the places were the Westphalian Peace treaty was signed. Being formally a war of religion (with strange coalition like the Catholic French king and the Protestant Swedish King fighting together against the Catholic Habsburg Emperor), the Peace treaty mainly ended the period of religious wars between Protestants and Catholics on the continent, together with giving important countries like the (Protestant) Netherlands, who had fought a 70 years war against (Catholic) Spain, or Switzerland (as a religious diverse country with Catholic and Protestant areas) their independence. The remembrance of this Peace treaty – one of the most important occasions in German/European history – is still very alive in Münster (not only because it is a good way to bring tourists to the town…).

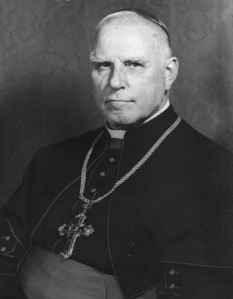

After the unification of Germany in 1871 under Bismarck the Catholics in Münster found themselves as a suppressed minority in the Protestant dominated state of Prussia and there were strong political conflicts between them and the central state, because they felt their religious rights were supressed. In this time it must have been very hard as a non-Catholic to live in this area, but the scepticism of the citizens of Münster towards the Prussian state and the strong Catholic tradition orientated towards Rome resulted in a much weaker (still too strong…) support for the Nazis in the elections during the Weimar republic, than in predominant Protestant areas. The support of the citizens gave the bishop of Münster, Clemens August Graf von Galen, during the Nazi regime the possibility to speak up against some of the crimes against humanity committed by the government and the Germans.

After the war the student dormitory that I lived in for five years was founded. This place is special, because the students living there are always 50% from Germany and 50% from abroad (and 50% male and 50% female…) and so people from all cultural backgrounds are living together under one roof. Run by the protestant church it is not a requirement to be Protestant or Christian or of any other particular faith or of any faith at all to live there. This concept creates a very special atmosphere and is from my point of view a good way to build good relationships and peace between people of different backgrounds. During my time in Münster there were a couple of occasions when right-wing extremists wanted to demonstrate in the town. At this occasions there were always huge crowds of people gathering to demonstrate for the rights of minorities, freedom and a social and democratic society. Usually there were far more then then times as many people demonstrating against the right-wing extremists than with them.

Knowing this long tradition of peacebuilding and anti-extremist behaviour it was not a surprise when in last autumn after the general elections in Germany it was announced that Münster was the only place in the whole of Germany where the far-right party AFD (Alternative for Germany), which stands mainly for anti-islam and anti-refugee populism, gained less than 5% of the total votes.

Coming back to the attack with the van last Saturday it was good to see that most citizens where ready to help, so that the police could thank them for their support afterwards and the hospitals could get so many blood donations in a short time that they had to send away people.

In my opinion the civic tradition of peace building and challenging any kind of extremism in Münster is a good example for all towns and cities in our world and maybe this story of a usually not very important (it’s not Berlin or Cologne or any other of the German cities) and it’s impact on world history can be inspiring for people else where in the world.