This week I witnessed two short (very uncontroversial) discussions about the political element in interfaith dialogue. One was about Holocaust Memorial Day, which will be next week, and one about the engagement of faith communities and interfaith organisations against climate change. Having this in mind I want to reflect today about how political interfaith engagement can/should be. I thereby reflect only about the situation in Western democracies. The situation in other kind of states might differ in several points and is to complex to reflect it here.

Interfaith Engagement is always political

The word “political” comes from a time when there existed a lot of different City States (polis) in Ancient Greece. “Political” in its basic meaning is therefore something, that regards the “affairs of the cities” or of the community/society in a specific area.

Interfaith engagement how I experience it here in Scotland has always the aspect of serving the community: It is always about building peace and and a deeper understanding between different religious groups and that is in the end a way of serving the whole community. The Scottish government has realized this and is therefore funding the work of Interfaith Scotland, what I consider as a great example, that other governments in the world (Hello Germany!) should follow!

Furthermore have all the different faith traditions a tradition of political engagement. Be it in the way of building religious dominated states in history or presence or important contacts between representatives of religion and state. That’s completely logical, because the religions claim to be important for the whole live of their believers – and the social/political life is a part of this.

When is political engagement dangerous for interfaith dialogue?

Not every political engagement of partners in interfaith dialogue is good. Should a particular religious group have to close political connections to a political party it might damage their credibility. If religions want to be political in the above meaning – and from my point of view they have to – they should fight (peacefully in a democratical system) for their goals in society, whether they rather fit with the agenda of the government or the opposition.

Of course for an interfaith organisation like Interfaith Scotland that is even more difficult. What if two or more members or dialogue partners follow different political agendas? Well in this cases it is not possible that Interfaith Scotland supports one of the two agendas. It could only make a statement that shows the differences between its members. In general it would be dangerous, if political statements could be made with a simple majority in a vote, for example between the members of Interfaith Scotland or its board. It would be recognized if for example the faith communities in Scotland would all together criticise the government and therefore such statements need a large majority or better a unity behind them. How can you find such a majority or unity? Well I would say dialogue is the answer!

It would also be dangerous for Interfaith Scotland, if it depended to much on one political party. If for example the Scottish government tries to influence the religious groups too much via Interfaith Scotland and would threaten to cut the funding, when they are not successful in that, it would not be possible to provide a neutral platform for interfaith dialogue.

Why and when is it good, that Interfaith dialogue is political?

Interfaith dialogue is political in a good way, when it brings people together for improving the society – and is successful. One example is Interfaith Glasgow’s Weekend Club where an interfaith group of volunteers organizes activities around cultural and religious themes for refugees and asylum seekers. The engagement for refugees and asylum seekers is definitely political in the meaning I mentioned above. It has definitely an impact on the society when refugees and asylum seekers feel welcomed in Scotland and if they have the chance to learn about Scottish culture. It has also an impact on the volunteers, who have the opportunity to learn from each other and the participants at the events. Through projects like the “New Scots strategy” or media coverage around One Big Picnic or the Family Fun Day Interfaith Glasgow raises the voice for refugees, asylum seekers and more justice in our society and that is definitely a good result of interfaith engagement.

Other examples where interfaith engagement has an impact on the society is Scottish Interfaith Week. Not every theme in every year is in the same way political, but for example “Care for the environment” in 2015 or “Religion and the Media” in 2016 or “Connecting Generations”, which might become the theme for 2018 have been and are political in a good way.

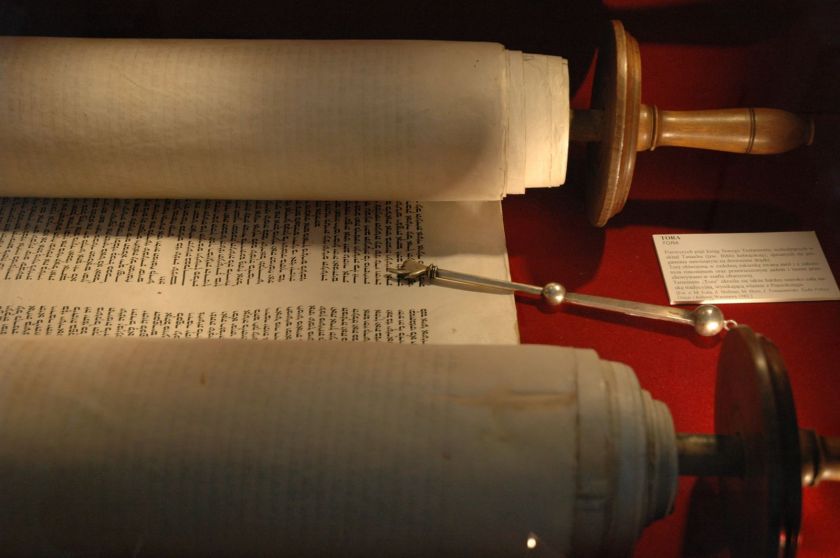

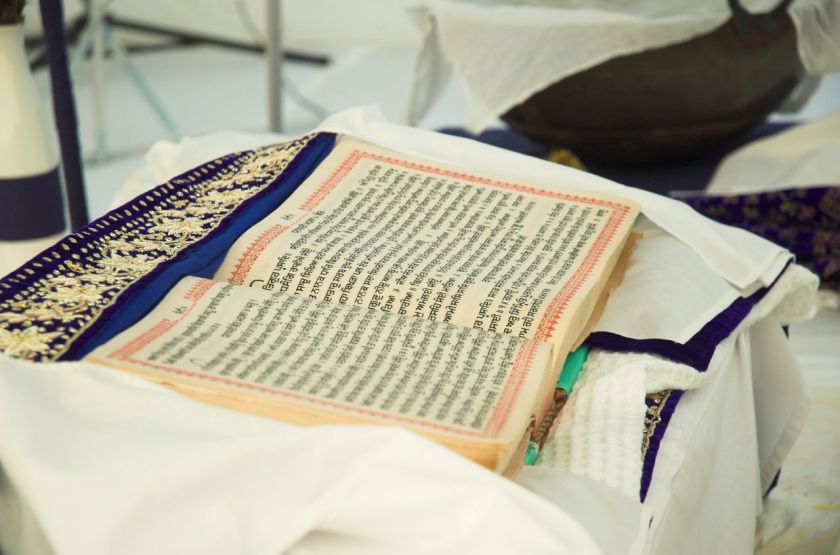

But it is important to realize that every religion has a different way to treat their Holy Scripture(s). My personal faith tradition started 500 years ago with Martin Luther’s idea of sola scriptura (religious truth is only in the scripture and not in the tradition or decisions of the pope) and it was the protestant church with its very academical way of thinking which invented the “historical-critical method” from the 17th and 18th century CE onwards. Today even other Christian churches, as for example the Roman-Catholic Church, have accepted the historical-critical method, but other Christian communities for example different evangelical free churches have not. In other faith traditions, for example Islam or Hinduism, they have a very different way of dealing with their Holy Scripture(s). A friend of mine wrote his dissertation at the end of his studies in theology (equivalent to a master thesis) about this topic and it was very interesting for me to see the different ways faith communities use their scriptures, but it even showed me that an interfaith dialogue about scriptures might not be as easy as I or the Archbishop Michael Fitzgerald are thinking.

But it is important to realize that every religion has a different way to treat their Holy Scripture(s). My personal faith tradition started 500 years ago with Martin Luther’s idea of sola scriptura (religious truth is only in the scripture and not in the tradition or decisions of the pope) and it was the protestant church with its very academical way of thinking which invented the “historical-critical method” from the 17th and 18th century CE onwards. Today even other Christian churches, as for example the Roman-Catholic Church, have accepted the historical-critical method, but other Christian communities for example different evangelical free churches have not. In other faith traditions, for example Islam or Hinduism, they have a very different way of dealing with their Holy Scripture(s). A friend of mine wrote his dissertation at the end of his studies in theology (equivalent to a master thesis) about this topic and it was very interesting for me to see the different ways faith communities use their scriptures, but it even showed me that an interfaith dialogue about scriptures might not be as easy as I or the Archbishop Michael Fitzgerald are thinking. I as an academic protestant theologian would read the Quran as a document from Arabia from the 7th century CE in which I find a lot of similarities and some differences to the Bible. And as in the Bible I might find texts in it, which I like and texts which I don’t like. I would assume that this point of view does not exactly fit with the point of view about the Quran of many Muslim believers. On the other hand the view of a Muslim on Biblical texts might really differ from my view on the text.

I as an academic protestant theologian would read the Quran as a document from Arabia from the 7th century CE in which I find a lot of similarities and some differences to the Bible. And as in the Bible I might find texts in it, which I like and texts which I don’t like. I would assume that this point of view does not exactly fit with the point of view about the Quran of many Muslim believers. On the other hand the view of a Muslim on Biblical texts might really differ from my view on the text. Does that mean that there is no sense in having interfaith dialogue about Holy Scriptures? No! It just means, that the dialogue might be not very easy – but I would think that the most people expect it to be easy anyway. The Holy Scripture(s) are for many believers the most precious texts in the world and because of this importance it might not to be easy to be open to different opinions. But that is not only the case in interfaith dialogue but also in dialogue about texts between believers of the same faith tradition. I would assume that it would be enriching to hear what how believer of different faith traditions read texts of the Christian (protestant

Does that mean that there is no sense in having interfaith dialogue about Holy Scriptures? No! It just means, that the dialogue might be not very easy – but I would think that the most people expect it to be easy anyway. The Holy Scripture(s) are for many believers the most precious texts in the world and because of this importance it might not to be easy to be open to different opinions. But that is not only the case in interfaith dialogue but also in dialogue about texts between believers of the same faith tradition. I would assume that it would be enriching to hear what how believer of different faith traditions read texts of the Christian (protestant