On Wednesday Adama Dieng, the UN Secretary-General’s Special Adviser for the Prevention of Genocide, visited Interfaith Scotland for a dialogue event. He presented the UN’s “Plan of Action for the Prevention of Genocide”.

In the dialogue he realised that a lot of good practise that he encourages people all over the world to do is actually already happening in Scotland. The plan of action addresses mainly (but not only) Religious Leaders and Actors. For me this gives me an opportunity to reflect a bit on the role of religious leaders for interfaith dialogue and genocide prevention.

The connection of interfaith dialogue and genocide prevention

For me the prevention of genocides and religious violence is one of the most important motivations for interfaith dialogue. Good interfaith relationships are probably the best way to prevent religious motivated hate crimes (and the genocide is the worst form of a hate crimes). In the Holocaust, as well as in the persecution of Baha’i in Iran or Rohinga Muslims in Myanmar religion was/is one of the motivations for the committed crimes.

The important role of religious leaders for interfaith dialogue

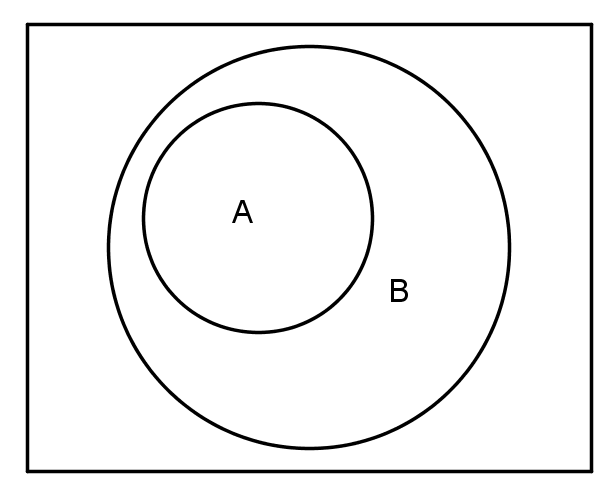

Faith communities are structured in very different ways. They can be very hierarchical or with a very flat hierarchy. They can be structured top-down or bottom-up. Nearly all faith communities have some kind of persons that are responsible for representing them at different occasions.

It is very different how much “power” the different religious leaders have in speaking for their community, but what they are doing as representatives is usually highly symbolic. When religious leaders for example meet people from other religions this usually has an impact on how the public and people from their own religion see the relationship to people of other religions. Depending on the structure of their faith community religious leaders are also able to “set themes” for the discussion inside their community.

One difficulty with religious leaders can be that not everyone in their faith community might be excited about a larger interfaith engagement. Because of that it is possible that certain religious leaders can’t go as far forward with their actions as they might wish to do, because they have to respect and also represent those members of their community that are not interested in interfaith. Another difficulty for an interfaith dialogue between faith leaders can be that in case a leader is not very much interested in interfaith themselves it can handicap the initiatives of those members of their faith communities who want to drive interfaith forward.

How I experienced the religious leaders in Scotland

The religious leaders of Scotland meet twice a year together and a third time for a joint summit with the first minister. Interfaith Scotland is functioning as secretary for those meetings. I personally had the opportunity to participate in those meetings as a note taker. The actual content of the meetings should not be shared here but it is possible, to give some of my impressions.

1) The religious leaders seem to appreciate the cooperation with each other. The meet each other very open and respectful and a lot of faith communities large ones and small ones were represented.

2) The religious leaders are talking open with each other. At the meetings they tell openly about what is going on in their communities. As far as I could witness it there seems to be a true base of trust between them.

3) The religious leaders cooperate with each other. At points that concern all/some of the faith communities they work together. For example were most of the face communities and their representatives involved in an event about the risks of climate change at the Scottish Parliament some weeks ago or they show solidarity if one faith communities suffers from certain problems.

That the leaders of the faith communities are working so good and smoothly together is not usual, especially on a world wide perspective and Scotland can be proud about the process of cooperation which has been made in the last years.